(if you are viewing this via email, the website has a recording of this poem and commentary; click the title above)

Commentary

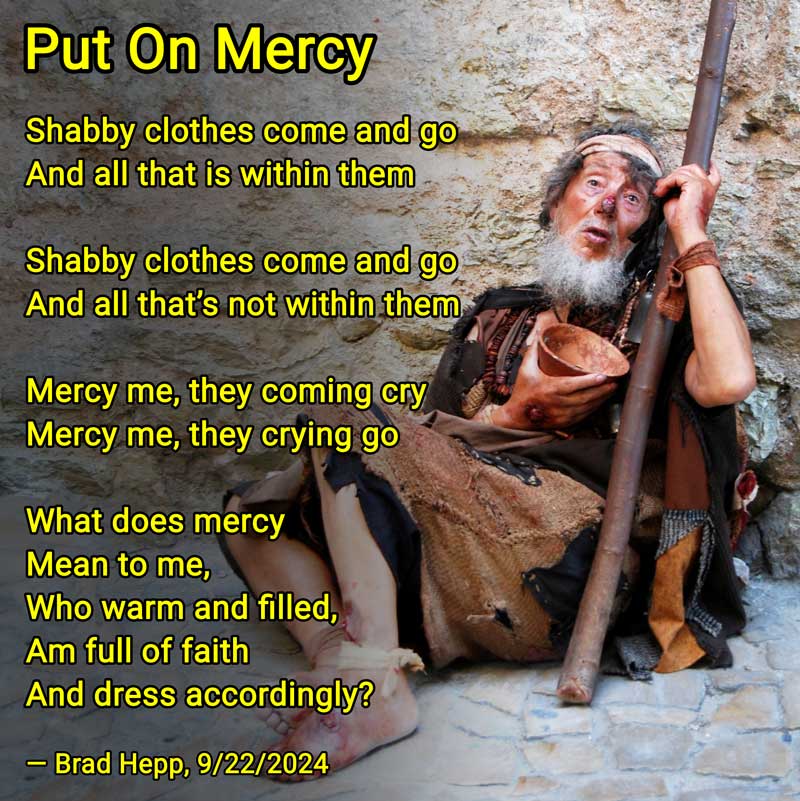

In his letter to Jewish believers scattered throughout the Roman Empire, James has his readers imagine their response to a poor man walking into their church. Something I hadn’t noticed until this morning is that James has the poor man coming in AND going out in shabby clothes.

First the coming in:

For if a man wearing a gold ring and fine clothing comes into your assembly, and a poor man in shabby clothing also comes in…

James 2:2

And then the going out:

If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, and one of you says to them, “Go in peace, be warmed and filled,” without giving them the things needed for the body, what good is that?

James 2:15-16

The verses between this coming and going talk about impartiality. If you’re like me, you interpret that as “Don’t treat the rich visitor better than the poor visitor.” But James goes beyond such passive impartiality. He wants to know what you’ve done for that poor man between the welcome and dismissal, between the coming and the going. Are you sending him off just as poorly provisioned as when he came in? Notice the last of James’ examples of proper, faith-fueled hospitality:

And in the same way was not also Rahab the prostitute justified by works when she received the messengers and sent them out by another way?

James 2:25

Some Things to Notice in This Poem

First, the title “Put On Mercy” has two meanings. The Apostle Paul urges believers

Therefore, as the elect of God, holy and beloved, put on tender mercies, kindness, humility, meekness, longsuffering;

Colossians 3:12 (NKJV)

That’s the first meaning of “Put On Mercy”: be clothed in a virtuous manner of life.

But sometimes we fake it. Then our would-be virtue might just be put-on mercy: fake mercy.

In the last stanza, I cast doubt on whether or not the speaker is really putting on mercy. The speaker is assumed to have faith. Does he dress accordingly? Really? He’s warm and filled. Does merely wishing the same for the poor visitor amount to mercy?

Second, “shabby clothes” in this poem are an impersonal shell for the unloved, ignored visitor. The words don’t even acknowledge the person, but refer to him or her as “all that is–or, in poverty is not–within them.”

Third, “mercy me” is an odd phrase. We utter it to express alarm or agitation. But what if some non-standard English speaker thought that it constitutes an actual plea for mercy. Could we hear it that way? Would we respond with God’s mercy? Or would the mendicant leave without our response?

Finally, “all that is within” may serve as a faint bit of fake holy talk. It echoes a well-known Psalm:

Bless the Lord, O my soul,

and all that is within me,

bless his holy name!Psalm 103:1 (ESV)

[Does that commentary help you understand the poem better? I’d love to hear from you! (If you received this poem via email, click on the poem title. That will take you to the blog where there is a comment form. If you’re shy in your response, just respond to the email!)]

(background image based on a photo by Gianni Crestani on Pixabay)